Schenes

Northern California (USA) | February, 2026

Photographer: Marie Clarke

A workshop where a 1960s drag racing club finds new life, carried forward through passed-down tools, worn benches, and work made to last.

“You don’t keep something like this alive by chasing perfection. You keep it alive by using it and letting it grow with you.”

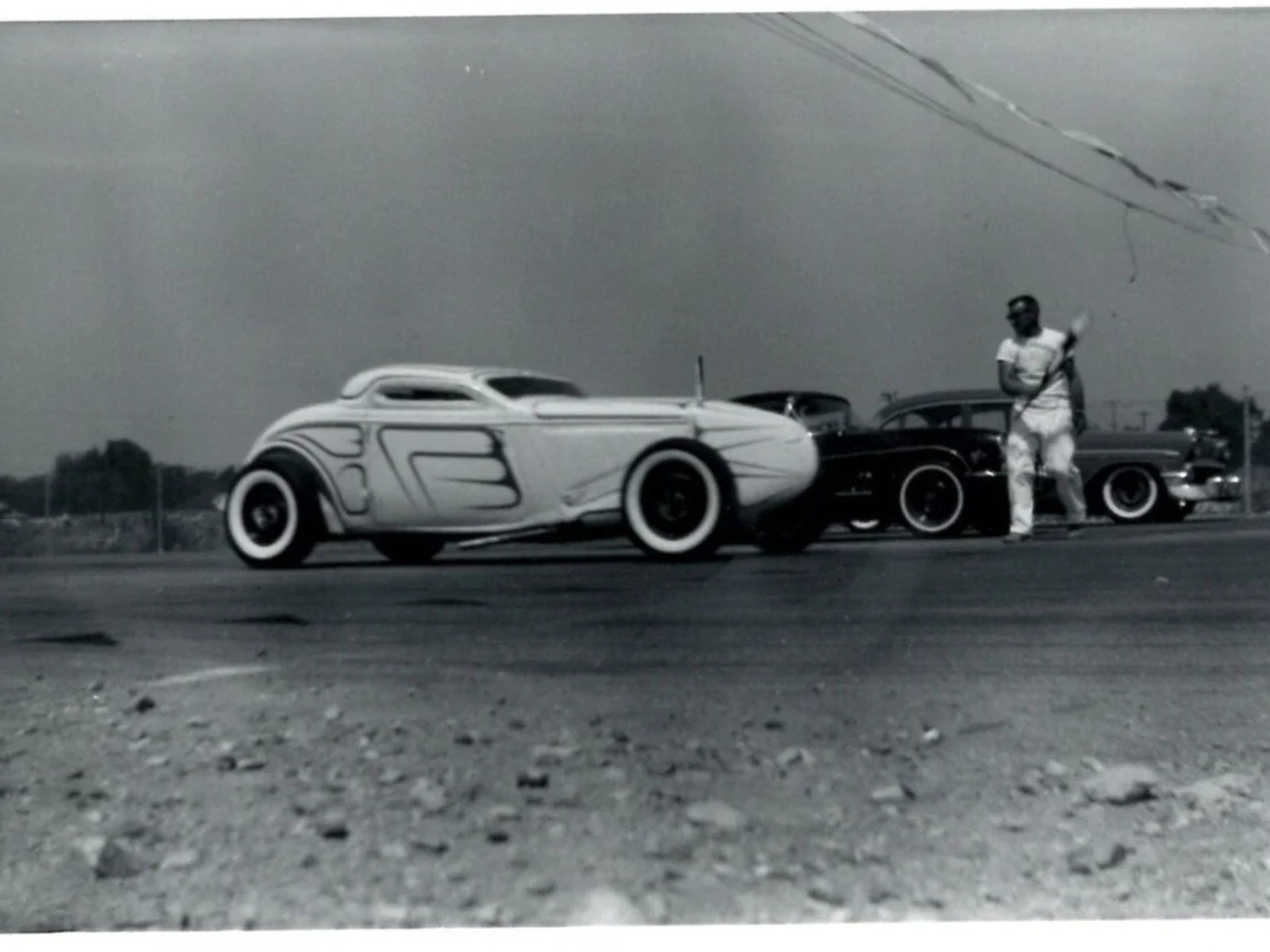

In the early 1960s, Schenes wasn’t a clothing label.

It was a car club. A drag racing team. A committed group built around machines, late nights, and the belief that if something was worth running, it was worth fixing yourself. Schenes lived in garages and swap meets, at the strip and on the side of the road, wherever people gathered around cars that demanded attention and rewarded care.

Jim Bray was an early member of that world, a mechanic through and through. Someone who understood the machines well enough to keep them alive. He was a builder, a problem solver, and later, a grandfather who never stopped working with his hands.

Decades after the club faded, the tools remained. So did the mindset. Jim spent the later part of his life repairing and restoring what others had written off. He believed in dependability. In the kind of quality that came stamped with “Made in the USA,” not as a slogan, but as a promise.

His grandson, Zander, grew up steeped in those lessons.

“Schenes started as my grandfather’s car club. Keeping the name alive felt like the most honest way to keep him close.”

Zander learned how to use tools and work on things in his father’s shop. His father was a prototyper and machinist, with a workshop at home that functioned less like a pristine lab and more like a constantly evolving archive. Materials were rarely bought new. Instead, they were collected, pulled from trash, estate sales, company closings, and anywhere else something useful could be rescued.

When Zander was younger, he carved out a small corner of that shop for himself. It wasn’t official and it wasn’t much. A tiny workbench where he’d come home from school and make things, experiment, and learn by doing.

From his grandfather, he learned something different but just as important: the value of quality, of keeping things alive instead of replacing them. Of choosing care over convenience.

Every Saturday with Jim meant a swap meet. Old tools. Forgotten parts. Mechanical oddities most people walked past. Jim never did. They’d bring something home and rebuild it together. No instructions. No rush. Just patience, curiosity, and the quiet satisfaction of fixing something properly.

When Jim passed, the shop went quiet.

Zander’s mother couldn’t bring herself to go through it. Too many memories. Too much history. So Zander took it over instead. The space felt suddenly barren, emptied of the person who gave it meaning, but that absence created room for continuity.

This is where Schenes began, again.

For the first time, Zander had a legitimate space of his own. His own set of tools and room to work. Freedom to create, rebuild, repair, and experiment without borrowing corners or packing things away. What had once been learned in fragments suddenly had a home.

At first, the garage lived in two worlds at once. On one side, VW motors were torn down. Choppers took shape. On the other, fabric and patterns emerged, clothing stitched together. Mechanical work and garment making happening side by side, driven by the same instinct: take something apart, understand it fully, rebuild it with intention.

Zander grew up surrounded by old things. Antiques. Objects with stories worn into them. Blank white walls never made sense to him. Inspiration mattered. Texture mattered. But function mattered most. This wasn’t a styled workshop pretending to be real. It was a working one, with lathes, bandsaws, and tools stacked with purpose. Everything here earned its place.

The modern iteration of Schenes officially took shape just over a year ago. August 1st, 2024. The first sketches. Zander was nineteen when the idea crystallized, twenty-one now. The brand is still growing slowly, organically, and self-funded. Zander is still working other jobs to support it. Full-time in commitment, if not always on paper.

And it didn’t take long to outgrow the garage.

Cars weren’t always the focus. Growing up, Zander didn’t care much about them. That changed when a childhood best friend bought an old beater BMW. One day, out in a dried riverbed, his friend took him for a ride and started doing donuts. The dust, the noise, the lack of rules - it all clicked. Cars stopped being just objects.

Schenes is rooted in classic cars and motorcycles, not vehicles of necessity, but of choice. “If you see a classic or vintage car still on the road, someone took the time to care for it,” says Zander. Those are the same people the brand speaks to. The clothes are meant to be worn, worked in, repaired, aged. To carry your story the same way his grandfather believed machines should.

The operation remains small and the goal clear: produce vintage-inspired workwear for people keeping car culture alive, while collecting and sharing the stories behind the machines they refuse to let disappear.

Cars and clothes are intertwined for him. As a kid, he’d take jeans apart just to see how they were made, studying seams, construction, wear, and then stitch them back together. That curiosity led naturally to workwear: Dickies, Carhartt, Ben Davis. Skateboarding filled in the rest. Long days skating, subcultures overlapping, learning that style grows from function, friction, and community.

Anything made by hand still holds his attention. Art. Music. Design. The common thread is intention, someone choosing to build rather than consume.

Today, the shop is a two-car garage dense with history. His favorite tool is a leather belt-driven lathe from the 1940s, inherited, still turning metal like it always has. No romance added. It earns its reverence by working perfectly, decades later. Two matching red leather couches sit against one wall, a Craigslist find from another life, likely ’70s vintage. No provenance. Just right.

One of his favorite memories here centers on a motorcycle that nearly destroyed the place. An orange-and-black Honda CB200, his first bike bought on a whim in Lake Tahoe for $200. It came home and immediately came apart. Carbs rebuilt. Systems cleaned. The gas tank was rusted beyond reason, so he filled it with vinegar to strip it clean. The final step was neutralizing the acid with baking soda.

A friend skipped a step.

The result was a five-foot vinegar geyser erupting inside the shop. Foam everywhere, acid in the air. A year later, he’s still finding residue in the corners. It’s the kind of story every real workspace carries - the cost of learning by doing.

Soul music usually fills the room. Samples. Deep cuts. Always playing, silence doesn’t belong here.

Most of the tools were inherited. Zander’s probably only bought a few hundred dollars’ worth himself. The rest came from the same hands that taught him how to use them. His favorite hammer is one he bought with his grandfather at a swap meet years ago. Rusted when they found it - they cleaned it, re-handled, and put it back to work.

That lesson never left him: you don’t need the fanciest equipment. You need time. Care. Attention.

Creative spaces matter, not as showpieces, but as mirrors. Bike builds. Car restorations. Clothing. Art. Every workshop tells you exactly who someone is and how they move through the world.

This one tells a clear story.

It’s not about nostalgia for its own sake. It’s about stewardship. About carrying a name, a mindset, and a way of working forward so they continue doing what they’ve always done.

Schenes may be young again.

But it’s certainly not new.